The effect of Instagram on Contemporary Art: Instagramization and the rise of the Instagram-Experience

In June of 2018 Instagram reached 1 billion ‘active users’, more than 500 million of these using the app on a daily basis. The photo-sharing app has become an everyday part of the lives of its users, as well as the never-ending stream of businesses, influencers, pets, cgi-generated characters, and bots who call the app home; but in the 10 years since Instagram launched, has the social media platform changed how we live our lives outside of our posting habits?

In recent years there has been a rise in, what has been described as, an instagramization of cultural spaces: from changing designs of restaurants, café’s and shops to museums, art galleries and purpose-built, instagramable installations. The changing look of restaurants and café’s is an appropriate place to begin a study of this; the food industry was an early adopter, or potentially an early victim, of Instagram. A clearly identifiable feature from the early stages of this shift was the boom in coffee art. While coffee art can be traced back to it origins sometime in the 80’s, there has clearly been a significant boost in the last few years, spurred on by Instagram, the hashtag #CoffeeArt has close to 3 million posts attached to it, many of the most popular coming directly from baristas and accounts linked to coffee shops. A well received image on a hashtag like #CoffeeArt, #CoffeePorn, or #CoffeeLover has the power to boost business in a way only previously obtained from a well crafted, expensive and time-consuming ad campaign. However, in recent years the instagramization has gone further than extra attention being paid to cappuccinos, some restaurants have began to create specific menu items designed for Instagram appeal, ‘Rainbow-coloured “unicorn foods” are often designed with Instagram in mind, and entrepreneurs responsible for popular treats like the galaxy donut and Sugar Factory milkshake often see lines around the block after images of their products go viral’ (Newton, Casey. 2017). This shift in the philosophies behind designing a menu is a clear response to the rise in food photography on Instagram, which in turn has further fueled more Instagram users to post pictures of this Instagram tailored food. These changing attitudes towards the food have also been mirrored in the design approach of restaurants and café’s themselves, physical spaces are being designed to make an impression on an Instagram feed. Take for example, the hugely popular Sketch London in Mayfair, everything about this restaurant, from the much photographed pastel pink chairs to their space-pod themed toilets, has been designed to create a clear visual brand, easily identified on an Instagram post.

This new approach towards design spans across many different areas of our lives, not only are our favourite restaurants no longer candle lit and romantic, but now exhibition spaces and even certain types of art are seemingly being designed with Instagram in mind.

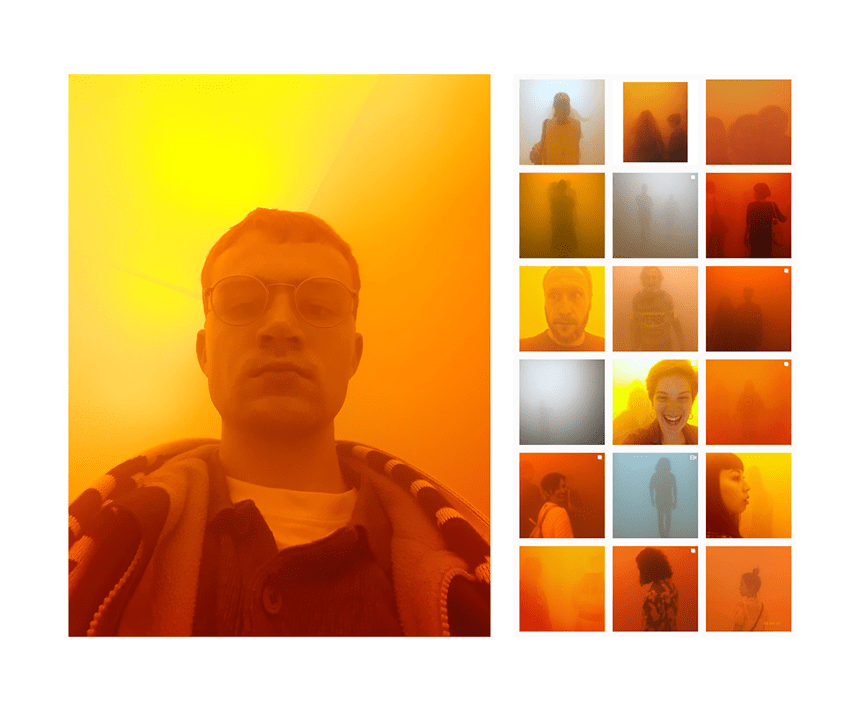

Take for example the recent Tate Modern retrospective on Danish-Icelandic artist Olafur Eliasson, In Real Life. This incredibly popular exhibition ran from the 11th July 2019 to the 5th January 2020 and during this time Instagram was awash with orange-tinged selfies from an installation at the centre of this exhibition, Din blinde passager (Your blind passenger), a 39 metre long, fog filled corridor. Once inside this corridor you are engulfed in a thick fog which fills the room, making everything beyond a metre and a half ahead of you impossible to see, over the course of the journey from one end of the room to the other the fog begins to turn orange and then blue, creating a uniquely uneasy and exciting experience as you slowly stumble towards the doors ahead of you. It didn’t take long for this installation to become a hotspot for selfies and Instagram posts, the hashtag #YourBlindPassenger containing close to 1000 of these other worldly selfies, while many thousands more occupy hashtags such as #OlafurEliasson, #InRealLife, and #TateModern.

This Instagram buzz for the exhibition generated such publicity for the installation that there were queues comparable to a theme park, filled with people eager to get that perfect image (myself included), skipping over artworks and installations designed to draw attention to issues such as climate change, energy, and migration to instead get a good spot in the Instagram-popular tunnel of light and fog. Due to this incredible popularity, a neighboring room housing the 1994 work No nights in summer, No days in winter, quickly became something of a waiting room, complete with roped off rows for queuing. Instagram popular installations such as this have become a divisive topic, some arguing that the huge digital footprint that art works such as Din blinde passager have can risk cheapening the experience for other art goers. This fear for the experience to be soured by a mass of images online led James Turrell to request visitors not to take photos of his 2013 installation at the Guggenheim, this request was ignored and approximately 5,000 photos were shared to social media, becoming the most Instagramed work from the Guggenheim at the time. Nora Atkinson, a curator at the Renwick Gallery, has expressed concerns that the obsession with photo-opportunities and the works being experienced through a smartphone camera does have a risk of denying visitors ‘a deeper experience of the art’, however it is undeniable that the growing presence of Instagram and the mass sharing of images has led to the work being accessed by people who wouldn’t have otherwise visited. In Real Life, for example, was one of the most popular exhibitions at the Tate in recent years, helping to push the Tate Modern to the top spot as most visited attraction in London during 2019.

Installations which have benefitted from and seemingly been designed for success on Instagram aren’t limited to In Real Life; in 2015, reopening after 2 years of renovations, the Smithsonian’s Renwick Gallery became home to the large-scale sculptures and interactive installations of the Wonder exhibition. The Renwick Gallery, the first building in America exclusively built for housing art, was filled with custom-made, site-specific pieces, designed to best utilize the newly refurbished spaces by 9 leading contemporary American artists such as Leo Villareal, Patrick Dougherty, Jennifer Angus, and Chakaia Booker. These installations were all linked by their use of unexpected materials, on the Smithsonian website some of these works are described; ‘Jennifer Angus covered gallery walls in spiraling, geometric designs reminiscent of wallpaper or textiles—but made using specimens of different species of shimmering, brightly-coloured insects. Chakaia Booker spliced and wove hundreds of discarded rubber tires into an enormous, complex labyrinth as Gabriel Dawe hung thousands of strands of cotton embroidery thread to create what appear to be waves of colour and light sweeping from floor to ceiling’. This exhibition proved to be incredibly popular among Instagram users and selfies takers, generating 35,000 images being tagged to the gallery in the time the exhibition was open, while also bringing in the average yearly attendance for the Renwick Gallery in its first 6 weeks.

This sudden rise in instagramable art exhibitions and installations is made all the more alarming and sudden when you consider how up until around 5 years ago most museums and galleries had strict no photography policies. So what is responsible for this drastic shift? Many critics are quick to point their finger at the purpose built Instagram experiences such as now infamous Museum of Ice Cream. In her article on Instagramization, Emily Matchar describes these spaces as ‘the apotheosis of Instagramization, an entirely new category of cultural institution, the made-for-Instagram “experience”’(Matchar, Emily. 2017)

The Museum of Ice Cream first opened at its New York location in 2016 and was an instant hit, tickets selling out before construction was even complete, this popularity made the New York site a firm favourite for the selfies takers and Instagram users and led to the opening of another site in San Francisco. It describes itself on it’s website as,

“(transforming) concepts and dreams into spaces that provoke imagination and creativity. MOIC is designed to be a culturally inclusive environment and community, inspiring human connection and through the universal power of ice cream.”

Visitors of MOIC pay $39 for admission and are then given 90 minutes to explore the different rooms of the museum, pictures from the gallery largely consist of people submerged in a pool of plastic sprinkles, riding on a monochrome pink replica of a New York subway carriage and posing next to a huge plastic ice-cream scoop, however the museum does also boast ‘a magical floating table’, ‘an epic three-story slide’ and ‘a giant ‘Queen-Bee’ hive’. The museums founder, Maryellis Bunn, who in 2018 made Forbes’ 30 Under 30 list, denies the important role of Instagram in MOIC’s success, arguing that the museum has bigger aims and goals than simply being a hit on the app. However, despite Bunn’s denial, it is hard to not draw a link between the success of this venture and it’s appeal to Instagram users, the official account has over 400,000 followers and the hashtag #MuseumOfIceCream has close to 200,000 post associated with it, including photos from celebrities such as Jay Z and Beyoncé, Gwyneth Paltrow, Katy Perry and the Kardashians.

While Museum of Ice Cream may seem like a ridiculous concept and original yet gimmicky idea, it is far from unique; in recent years numerous spaces that serve a similar purpose have found success, having both a huge online presence and bringing in a mass audience of paying visitors. In 2015, during New York Fashion Week, the first of the ongoing 29Rooms popups opened, unlike MOIC, 29Rooms is not dedicated to one particular theme, each of the 29 room’s feature a different experience, the 2019 tour of popups featuring rooms such as The Art Park, Dream Doorways, and You Are The Magic. Piera Gelardi, the co-founder of Refinery29, the company responsible for the 29Rooms project, explains that the popularity of exhibitions and installations in classical museums such as Yayoi Kusama’s Infinity Mirror Rooms and Fireflies on the Water inspired the 29Rooms, ‘I thought there was an interesting opportunity for us to expose people to new types of artwork and concepts, but also create a space in which they could kind of be the star of the show.” (Pardes, Arielle. 2017). This model of taking the principle concepts of installations designed to put the viewer inside an experience, such as Kusama’s incredibly popular Infinity Mirror Rooms, which while exhibited at the Hirshhorn Museum in Washington were responsible for boosting membership at the museum from 150 members to 10,000 members, has led to the 29Rooms popups being well received at their various different locations; #29RoomsChicago having 2,596 posts attached to it, #29RoomsNYC having 1,639 and #29RoomsLA having 2,176.

While these spaces do bare some similarities to classic museums and exhibit pieces similar to installations by well-established artists, these spaces are often looked down at by the art-world. Art critic Christopher Knight describing these spaces as ‘manufactured entertainments (that) aren’t significant art exhibitions any more than a Chuck E Cheese arcade or the Block of Fame at Legoland’ (Pardes, Arielle. 2017), other reviews of these spaces are often critical of the fact that the names of the creators of the installations and pieces on show at these museums aren’t readily available. Instead of these Instagram-experiences being a space where the works of different artists are displayed to the public, with a view to educate and showcase, they simply display pieces which all come under their own brand. Regardless of whether or not the exhibits at these spaces are to be considered ‘art’, what many feel to be the biggest difference between somewhere like the Tate Modern and the Colour Museum is the aspect of profit and business, these Instagram-experiences are all for-profit organisations, each charging roughly $40 for entry. Many of the rooms and exhibitions of these spaces are also sponsored by companies, 29Rooms have included rooms such as Love Walk, a room made alongside Aldo, a Canadian footwear and accessary company, which featured arches made of Aldo branded shoes, while MOIC have worked alongside corporations such as Dove, Fox and Tinder.

However, this criticism of the corporate involvement and sponsorship seems hypocritical, galleries and museums have historically relied upon a certain level of corporate sponsorship, for example, since 2014 the Tate has been in partnership with Hyundai, and each year the Hyundai Commission hosts a large scale installation in the turbine hall of the Tate Modern. Historically the Tate has been reliant on involvement from corporations and businesses, in 1932 the Tate changed its name from the National Gallery of British Art to the Tate in honour of significant funding from sugar merchant Sir Henry Tate. While now mostly funded by the UK Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport, institutions like the Tate do also rely on membership, and exhibitions such as In Real Life and the upcoming Kusama exhibition do have entry fees for non members, typically around £5.

Regardless of the backlash and criticism that these spaces face, their popularity is clear, both on and offline. This popularity has been noticed by museum curators and owners, and in recent years many museums and galleries have started shifting into something more resembling these colourful, brightly lit and photograph friendly spaces. One key turning point in this shift from the museum and gallery space of 10 years ago to what is steadily becoming the norm for museums and galleries was photography now being allowed. Alongside this change in attitude towards the photography of works, in recent years ‘many contemporary institutions have changed their lighting from traditional spotlights to high-wattage fluorescent lights’ (Schwab, Catherine. 2016), while this is a subtle shift it represents a clear way in which photography is not only allowed but now being encouraged. Aside from galleries becoming more brightly lit and less aggressively anti-photography, what effect does this shift towards the sharing of images have on the art world. For some the answer would simply be that art is becoming more accessible, the high walls of the art world are being torn down, gallery owners and art dealers no longer get to determine the popularity and success of art, the power is now in the hands of what the people decide to share and like on social media. However, with this shift towards sharing art online come new concerns, prior to the advent of social media the art world was considered to be made up of image fundamentalists, those who believe that the meaning and value of an artwork was connected to its place of origin, and to separate the artwork from its original context was to remove the ‘aura’ of the work, and image neoliberals, who believe that art should be freely traded and moved, and that the meaning and value of art was in its ability to be shared and to reach the largest possible audience. Social media, and the mass sharing, reposting, re-blogging and retweeting of images, has led to a third group being established, image anarchists; in his essay Art After Social Media, Brad Troemel identifies the difference between image anarchism and image neoliberalism as ‘(behaving) as though intellectual property is not property at all. While the image neoliberal still believes in the owner as the steward of global migratory artworks, the image anarchist reflects a generational indifference towards intellectual property’ (Troemel, Brad. 2014. Page 38-39). For Troemel, the sharing of images without regard for intellectual property is leading to a disconnect between the artwork and the artist, images of art shared on social media platforms often being posted without reference to the artist responsible for the piece, the title of the work, or the date it was made. This lack of context given to the art has led to a paradox where the more popular an artwork becomes online, the more likely it is to not find any information about the artist included. In response to this, and in an attempt to reclaim ownership of the work, artists often have no choice but to get involved with the sharing of images, ‘using social media to strategically manage perceptions of their work – transforming it from a series of isolated projects to a streaming feed that transforms the artists’ identity into a recognizable brand.’ (Troemel, Brad. 2014. Page 39).

Long before the advent of Instagram Olafur Eliasson established himself as a popular artist. His work is often characterised by taking things found in nature and recreating them artificially to put an emphasis on their beauty, for example, his 2003 Tate installation The Weather Project which recreated the sun using monofrequency lights, projection foil, haze machines, mirror foil, aluminium and scaffolding. These simulated reproductions have always drawn in a crowd, in a review of The Weather Project from 2003, Dan Hill comments on the response that this piece got from viewers,

“What quickly became more interesting than ‘the sun’ itself – to me anyway – is the reaction of people to the project. I haven’t seen many pictures of people – perhaps because the sun’s so photogenic – which I find odd, given how it’s such an inclusive artwork, and people’s performance in that space is so much of the piece itself … First people stand and stare, wandering down the ramp of the turbine hall, barely able to believe their eyes, taking in the warm colours and misty atmosphere, drawn towards the sun. Slowly they look up and realise the ceiling is mirrored, increasing the ‘height’ of the turbine hall. People start to point and wave, trying to spot themselves, or simply stand and stare, lost in contemplation.” (Hill, Dan. 2003)

This summary of the crowds’ reaction to the piece is in line with what Timothy Morton, a philosopher who has worked with Eliasson in the past, identifies in Eliasson’s work. When describing Ice Watch, an installation which was displayed outside the Tate Modern in 2018, Morton identified an “obvious visual gag”, and ‘that the work is in fact “much more interesting” that this first layer of access might suggest’ (Souter, Anna. 2019). Just as the chunks of glacial ice in Ice Watch explored ‘our relationship with nonhumans in an age of ecological crisis’ (Souter, Anna. 2019), The Weather Project explored themes of self-image and ‘a desire to perform in public on several levels – both to be part of a crowd and to be individually reflexive’ (Hill, Dan. 2003). We can see in this piece that Eliasson’s work has always inspired audiences to explore their self-image and to discover their place in the artwork, and that while in 2003 viewers needed a large mirrored ceiling to do this, in 2019 posting selfies from the fog filled tunnel of Din blinde passager fulfils this same role. Looking back at this earlier work from Eliasson we can see how, while the Instagramization of the gallery space may be a modern phenomenon, a response to the growing popularity of Instagram-experiences, the work itself is not yet being moulded to match these trends.

However, unlike others who have written on the subject of the instagramization of the art world, I am not as positive for what seems to be the future. While it is clear that the work itself is not yet being altered to fit the trends of Instagram, it is also clear that Instagram-experiences such as the MOIC will likely continue to rise in popularity, and the crossover of audiences from these galleries and contemporary art galleries is concerning. Cultural institutions such as the Tate, the Guggenheim, and the Renwick Gallery changing their lighting and attitudes to suit the needs of a new audience isn’t such a negative, it is clearly bringing in a new audience, and while this new audience may be coming to the gallery intent on adding their orange selfies to the vast number of images shared on social media, they are also coming into contact with other, non Instagram friendly works. In 2014 Kara Walker, an artist whose work explores issues surrounding race, class, gender, and violence, unveiled a 75 foot tall naked sphinx statue at the Domino Sugar Factory in New York, this piece, which was created to reflect on black stereotypes, became very popular on Instagram, and many visitors, unaware of the pieces political message ‘photographed themselves pretending to play with the nipples and vulva of her 75-foot tall naked anthropomorphic mammy sculpture’ (Burke, Sharon. 2017). Throughout the months that the art was on display, Walker secretly filmed these visitors, who had flocked to the installation after seeing similar images on social media, and released the shocking footage in a 28-minute film, An Audience. The lack of understanding that this audience expressed when faced which a piece designed to challenge and address issues in contemporary America highlights how audiences who have become increasingly used to ‘art’ which exists solely to be selfied in front of are potentially only absorbing this art on a surface level, not willing to look deeper into the context that is so easily lost in an Instagram moment.

Bibliography

A. Souter (2019) ‘The Sprawling Ecologies of Olafur Eliasson’. Available HTTP: https://hyperallergic.com/

A. Pardes (2017) ‘Selfie Factories: The Rise of the Made-for-Instagram Museum’. Available HTTP: https://www.wired.com/

B. Troemel (2014) ‘Art After Social Media’ (pg. 36-43) in O. Kholief (ed) You Are Here: Art After the Internet. HOME, Manchester.

C. Newton (2017) ‘Instagram is pushing restaurants to be kitschy, colourful, and irresistible to photographers’. Avaliable HTTP: https://www.theverge.com/

C. Schwab (2016) ‘Art for Instagram’s Sake’. Avaliable HTTP: https://www.theatlantic.com/world/

D. Hill (2003) ‘The Weather Project’. Available HTTP: https://www.cityofsound.com/blog/2003/11/the_weather_pro.html

E. Matchar (2017) ‘How Instagram is Changing the Way We Design Cultural Spaces’. Available HTTP: https://www.smithsonianmag.

S. Burke (2017) ‘Its Time to Stop Hating on Museum Selfies’. Available HTTP: https://www.vice.com/en_