Horror films work with the threat and promise of the off-screen space. They play a game of withholding and revealing the image of the monster: a game in which the absence of the image is just as important as the image

The relationship between on and offscreen space is a fundamental aspect of cinema, and has been since 1926 when Renoir began to experiment with the form in Nana. In his essay on Nana, Noël Burch identifies the six segments of off-screen space. He breaks down these different elements of off-screen space into, the ‘four borders of the frame’, the space ‘behind the camera’, and ‘the space existing behind the set or some object in it’ (Burch, Noël. 1981. Page 17). The balance between what we, the audience, see in the frame and what the film keeps beyond the frame in these six segments is fundamental to creating a believable world on screen. Films before the illusion of depth was achieved now appear to resemble something closer to a stage production than to the real life they are trying to emulate; the actions all carefully kept within the frame and the characters typically all facing the camera. This is no longer the case, and Nana is often considered one of the earliest films to shift away from this, in Nana, ‘more than half of the shots (…) begin with someone entering the frame or end with someone exiting from it, or both, leaving several empty frames before or after each shot’ (Burch, Noël. 1981. Page 18).

There are many ways that the off-screen space can be introduced, techniques such as the entries and exits of Nana establish that there is more going on off the edges of the frame that we are not given access too. Burch also notes that the way in which Renoir hangs on the empty shot after a character has departed from the frame is what ‘focuses our attention on what is occurring off screen’ (Burch, Noël. 1981. Page 19). Another way in which off-screen space can be highlighted is to have a character look off to the distance. Shots which ‘(start) with a close up or a relatively tight shot of one character addressing another who is off screen’ (Burch, Noël. 1981. Page 20) make the offscreen space equally, if not more, important than the on-screen space. The third way Burch highlights how off-screen space can be defined is through the framing of the shot. Burch notes, it is ‘not until a disembodied hand enters the frame’ (Burch, Noël. 1981. Page 21) that the viewer becomes consciously aware of the off-screen space. In this essay Burch also defines the two different types of off-screen space; concrete and imaginary. Imaginary off-screen space being that which is left for the audience to picture for themselves, and concrete off-screen space being that which the film has established. Burch explains,

“when the impresario’s hand comes into frame to take the egg cup, the space he occupies and defines is imaginary – we do not know, for example, to whom this arm belongs. When in a subsequent shot the camera reveals the full scene, with Muffat and the impresario side by side, the space becomes concrete retrospectively.” (Burch, Noël. 1981. Page 21)

While off-screen space, both concrete and imaginary, have become a key part of cinema, it can be argued that in no genre is off-screen space used more frequently and to such effect as the horror genre. In this essay I shall look at the offscreen space used in It Follows (2014, David Robert Mitchell) and The Witch (2015, Robert Eggers). While these two films have different ways of utilizing offscreen space, the aim is the same, to position the monster – whether that be a witch or a shape-shifting invisible entity – in a game of being witheld and revealed. In doing this the films create tension and keep the audience engaged.

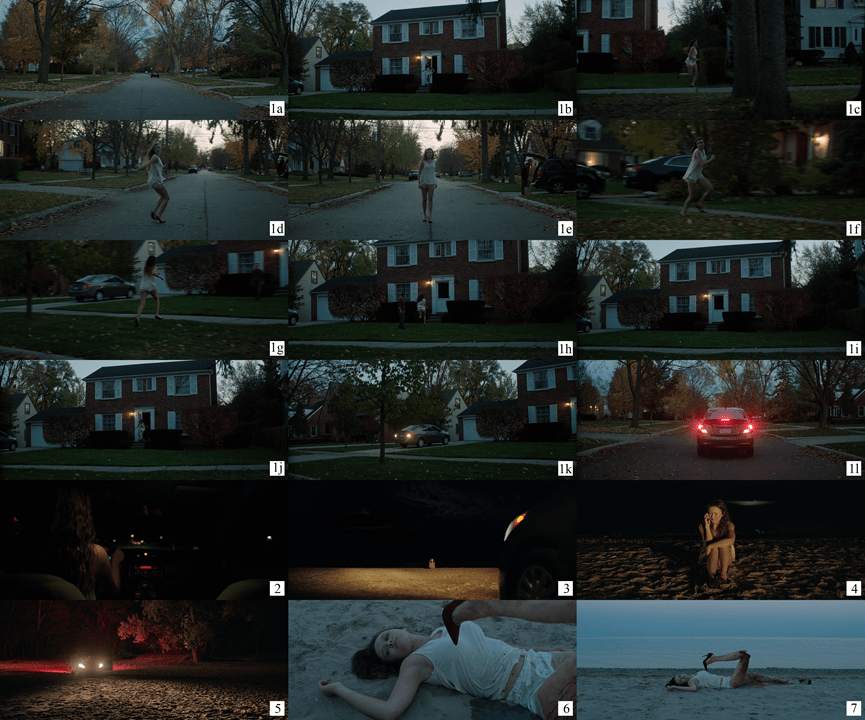

The opening sequence of It Follows clearly identifies the way in which offscreen space will be used throughout the film. In her essay on how trauma is represented in horror films Tarja Laine notes that ‘Thomas Elsaesser and Malte Hagener (2010) write that openings often cover the whole film in a nutshell, offering “watching instructions” that give the spectator a sense of what the inner dynamics of the film will be’ (2019. Page 287). These “watching instructions” are clearly present in the opening shots of It Follows. In the first shot of this sequence the camera slowly follows a girl who, in a state of panic, runs out of her house, loops around the camera – which pans around, following her journey – and then rushes back into her house, where, offscreen she presumably grabs her car keys, runs back outside and into the shot, gets into her car and drives away, leaving the camera on the street outside her house. The shot stays very wide and as it follows the girl around we get a clear picture of the space she is in, making the street where this takes place a fairly concrete location. However, at no point do we see what the girl is running from. This lack of a clear representation of what the girl sees, as well as the shot following the girl as she attempts to get away from whatever is pursuing her could suggest that this shot is from the monsters POV, however, the route that the girl takes seems to suggest that the monster came from inside her house and she draws it outside before running back in to get her car keys. Later in the film we find out that the monster in question is in fact invisible to those who are not in the position to see it, so this would explain as to why the monster cannot be seen in this shot.

The next shot in the sequence is from the backseat of the girls car as she is driving away, we then cut to a wide shot of the girl sat on the ground in an unidentifiable sandy area, she is illuminated only by her car headlights and on the phone to her dad, apologising for her behaviour and expressing her love for him and her mum. We then cut to a closer shot of her, before we see a wide shot of the car and the empty space behind the car, in this shot you would typically expect to see some sign of the monster, and from the soundtrack and the girls tone of voice it is clear that something is approaching, however this remains hidden. We then cut forward to the following morning and a close up of the girls corpse on a beach, from the following wide shot we can see her legs are both snapped and bent over. This sequence establishes the blend of concrete and imaginary offscreen space that continues to be used throughout It Follows. The offscreen space is identified quite clearly through the typically wide framing of the shots and the frequent movement of the camera, we have a clear sense of where the characters are and shots clearly lead into each other. However, despite the clear understanding of where the characters are, an important element of the scene is left imaginary; creating a concrete offscreen space where, despite being able to see the full surrounding area, we are still unable to see the monster, keeping it in the audiences imagination, therefore keeping the audience engaged with the film. These wide shots also have the effect of isolating the characters within them, Laine notes that they ‘isolate the protagonist in wide-open surroundings, rendering her vulnerable to uncanny, peripheral, invisible threat’ (2019. Page 284), the open space which surrounds the characters also suggests that the ‘threat seems to come from all directions at once, and (that) there is no escape’ (2019. Page 287).

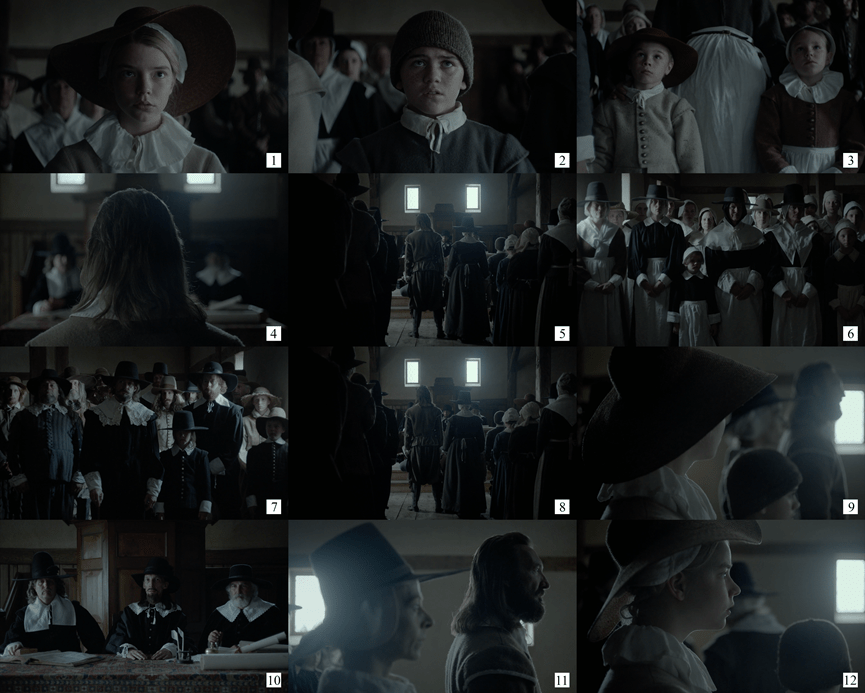

Like It Follows, the opening sequence of The Witch establishes how the film will go on to use offscreen space. The wide and swooping camera style of It Follows isn’t the only way horror films can utilize offscreen space, The Witch uses almost the complete opposite technique. Unlike the typically wide shots of It Follows, The Witch frequently uses a tight mid shot. The film opens on a close up of the protagonist, Thomasin, looking above the camera and listening to a conversation between offscreen voices. We then get similarly framed shots of her brother, Caleb, and her twin brother and sister, Mercy and Jonas, looking in the same direction and reacting to the offscreen voices. After these three shots we get a shot from the back of her fathers head, obscuring the view of the people they are stood listening to, before cutting backwards to a wide shot from behind the whole family. At this point very little information has been given in regard to the space they are in, but from the conversation and the characters facial expressions it becomes clear this is a trial and that Thomasins father is being facing the consequence of a religious dispute. Following these shots we have two shots of the surrounding crowds, these shots cement the space, position the family as distant from the community that surrounds them and give us a wider view of the world this film takes place in. We then return to the shot from behind the family standing trial, in front of the family, slightly obscured from view and just out of focus, the source of the previously faceless voices can be seen, as the family are declared guilty and banished from the plantation we cut to a close up from the side of Thomasin, alongside her, just out of focus we get the first look at her father as he responds to the verdict, before we finally get a clear shot of the Governor who has passed the sentence, we then return to a closer side view of Thomasin’s mother and father who leave the frame, followed by their children.

This entire sequence is essentially a very delayed shot/reverse shot. In a typical sequence of this nature we would open with the shot of Thomasin looking offscreen, which would lead us into a shot of what it is she is looking at, the Governor. This is a way in which Noël highlights offscreen space being eluded to in his essay on Nana. However, by drawing out this sequence and not cutting to the reverse shot the space remains imaginary for longer, allowing more time for the audience to speculate as to what is going on. These delayed shot/reverse shot’s are continued throughout The Witch. Later in the film while Thomasin plays peekaboo with Sam, her baby brother, we get another example of this technique and at the key moment of this scene, where Sam is taken by the Witch, we hang on the shot of Thomasin looking down in horror for 6 seconds before cutting to the empty space where Sam previously was. In this absence of a reverse shot the sense of dread and suspense is built up, audiences are not told what has happened so are left to imagine it for themselves. This delay is typical of the horror genre, withholding the monster in this way means that the audience are left to fill in the blanks.

Unlike the slow and suspenseful tight shots of The Witch, It Follows draws on other framing devices to add tension to a scene, one such example can be found when Jay and Greg visit a school in an attempt to identify who passed the monster onto Jay. This scene of the film is played out in one continuous shot. The shot (sequence breakdown 2) starts off zoomed in through a window, focusing on a couple sat underneath a tree in the school grounds, the camera pans around while zooming out, revealing an unidentifiable girl walking directly towards the camera, it is to be assumed this is the monster, as this is the typical way in which the film has shown us the monster throughout the film, however this is not confirmed. The camera continues panning around across various extras stood in the hallways before we see Jay and Greg enter the frame, they walk around a corner and then go offscreen in the direction of an office area, as the camera continues its pan we see them appear at the desk in the distance where they hand over a photograph of the person they are trying to identify. The camera continues panning back around, now completing a full 360 degree spin, and we see that the girl is still walking toward the camera through the window, getting closer and closer, the camera spins around again, back to the school office area opposite the window, where it begins to zoom in on the receptionist picking up a stack of yearbooks and identifying the person Jay and Greg are looking for, they then both walk offscreen and back in the direction they came, the shot lingers on the receptionist for a moment longer the shot ends. This shot draws attention to and engages with all the different areas of offscreen space that Noël pinpoints in his essay, except maybe the space above and below the frame, characters enter and exit the shot from areas behind and in front of the camera, and the continuous spin means that the space to the left and right of the frame is shown to the audience. In having this scene play out in this way we are reminded of the rules that the film has established for the monster, that it can take the form of anyone, that it will constantly pursue you until you pass it on or destroy it, and that it can come from any direction. Any of the background characters we see walking around this shot could, in theory, be the monster, any of the doors and offscreen spaces that join up with the onscreen space could be where the monster next appears from. It is likely that the girl walking towards the camera in the distance is the monster, as this is the typical way in which we have previously identified the monster in the distance, a ‘sudden change of focus to a distant figure in the background’ (T. Laine. 2019. Page 286) has so far been how the monster has appeared in the film. However, leaving this as a mystery keeps the audience guessing, leaving room for them to engage with the film and speculate.

The film often uses different camera techniques to position the audience with certain characters, the dizzying spin of this previous sequence can be seen as a mirroring of the fear and mindset of those cursed in the film, constantly in fear of where the monster could next be lurking. Another moment where the film mirrors the characters mental state can be found at the beach sequence. This sequence opens with a fairly standard use of offscreen space. We open on a wide, establishing shot, showing the audience the location and the orientation of each character in the scene, we then cut into a series of close ups of each of the characters looking offscreen towards a different member of the group. This section of the sequence follows the typical A,B,A,B pattern of shot/reverse shot, where we begin on one character (A), cut on their eyeline to what they are looking at (B), return to the original character (A), and then finish on the other (B). Through following this well established convention of shooting a conversation, we get a moment where the film establishes the relationships between each of the characters using only the framing of the shots and the editing pattern, coupling up Paul and Jay, and Greg and Kelly. After this series of close ups, Greg departs from the beach area, walking behind Jay as he leaves the frame, in doing so drawing attention to an unidentifiable figure approaching in the background of the frame. As the figure approaches it becomes clear that it is Yara, the 5th member of the group who has been previously absent from this sequence. It is only in the next shot, a close up of Paul, when it becomes apparent that this approaching figure is not Yara. In the background of this close up the real Yara floats into frame on a rubber ring in the sea behind Paul. Unlike other moments when the monster has emerged in the film, this sequence waits until the reveal of the real Yara for ‘the jarring music (to) start off on the sound track, indicating imminent danger’ (T. Laine. 2019. Page 290). In withholding this musical confirmation that the approaching figure is the monster the audience are forced to enter into the paranoid and suspicious mindset that the characters in the film are forced to adopt, unsure and fearful of any approaching figure, even if it appears to be a friend. This sequence also reinforces that ‘every offscreen space, or every space beyond centre within the frame, (is) a space where the threat potentially emerges’ (T. Laine. 2019. Page 290).

Once it has been established that this approaching figure in the form of Yara is the monster we return to a typical shot/reverse shot sequence, where we cut between Jay, who is unaware of the approaching threat, and her younger sister Kelly, who despite being sat opposite Jay cannot see the monster. This sequence builds tension in the classical Hitchcock style, where the audience know what is happening but are forced to watch the characters blissfully unaware of the impending danger. Like a young Stevie on the bus in Sabotage (Alfred Hitchcock, 1936), clueless to the fact the film canisters he is carrying are concealing a bomb set to detonate in a matter of minutes, Kelly lounges on the beach, casually chatting about whether or not they should join the real Yara in the water, unable to see the steadily approaching threat. As the monster makes contact with Jay it is no longer present in the shot, instead we, like Paul, Kelly and Yara, see Jay’s hair mysteriously rising as the invisible monster grabs a handful. The monster remains invisible for the next few wide shots, where the real Yara runs into frame, Paul smashes a chair over where the monster presumably is and then gets thrown offscreen, and Kelly, Jay and Yara run to the safety of the beach house. It isn’t until we cut to a POV shot as Jay looks back at the monster that we see it again, still in the form of Yara. In making the monster invisible for this section of the sequence we are put into the same space as the surrounding characters, unable to see the monster but aware of it’s existence. In returning to this blend of on and offscreen space, where we know that something is present in the shot but cannot see it, we witness the power offscreen space has to ‘disturb and torment not only the protagonists but also the spectators’ (T. Laine. 2019. Page 283), the spectators being both the audience and the other characters in the film.

Like the known but invisible presence of the monster in this sequence, The Witch builds tension on the fact that the witch’s presence is established early in the film, we are aware of this witch while the family aren’t. Despite the presence of the witch being known, offscreen space is still used to build on this tension. While It Follows uses wide, frequently moving shots to establish a concrete yet mysterious offscreen space, where at any moment the monster could appear, or already be, The Witch works with a more imaginary offscreen space. An example of this imaginary offscreen space that The Witch creates can be seen towards the end of the film where the devil reveals himself to Thomasin, emerging from Black Phillip the goat. The horror that befalls the family has come to a climax with Thomasin killing her mother as she attempts to strangle her, Thomasin then enters the barn and commands Black Phillip to speak to her like he has spoken to her young twin siblings Jonas and Mercy, upon doing so an offscreen voice replies. This voice presumably is the devil, and while this voice instructs Thomasin to remove her clothes and sign her name in the book that appears before her we do not leave the medium close up of Thomasin, except from a cut to the book. We do get a glimpse of the figure which Black Phillip has transformed into as he walks into the background of the frame, but the figure remains very much imaginary.

To conclude, from these two films we can see that there is no set way in which offscreen space must be used; from the wide and sweeping shots of It Follows to the tight and slow shots of The Witch. Despite these different ways in which it can be used the rules of offscreen space which Burch identified in his essay always apply, and in this use of the 6 areas and 2 types of offscreen space the films manage to withhold and reveal the monster. This game which the film plays works to stop the film from simply being a machine delivering spectacle, making the film instead a non-stop display of horror. This game of withholding and revealing allows the audiences imagination to fill in the blanks, the longer this gap is left open the longer the tension is built, as soon as this gap is closed the audiences place in the film is lost, the version of the film which they have envisioned is replaced by the film.

Bibliography

It Follows (2014, David Robert Mitchell)

N. Burch (1973) ‘Nana, or the Two Kinds of Space’ in N. Burch & H. Lane Theory of Film Practice. Princeton University Press, New Jersey.

T. Laine (2019) ‘Traumatic Horror Beyond the Edge: It Follows and Get Out’ in Film Philosophy 23.3. Edinburgh University Press, Edinburgh.

The Witch (2015, Robert Eggers)