Comparing the découpage in The Testament of Dr Mabuse and The Dark Knight by examining a brief sequence of shots from each film

Both Fritz Lang’s 1933 ‘The Testament of Dr Mabuse’ and Christopher Nolan’s 2008 ‘The Dark Knight’ follow the actions of a criminal mastermind, unmotivated by money and seemingly insane, as they attempt to overthrow a city. While there are some narrative similarities between these two films, the techniques that the respective filmmakers use differ; Lang being an early adopter of continuity cinema and pioneer of visual rhymes and Nolan working in a Hollywood that is often described as post-continuity.

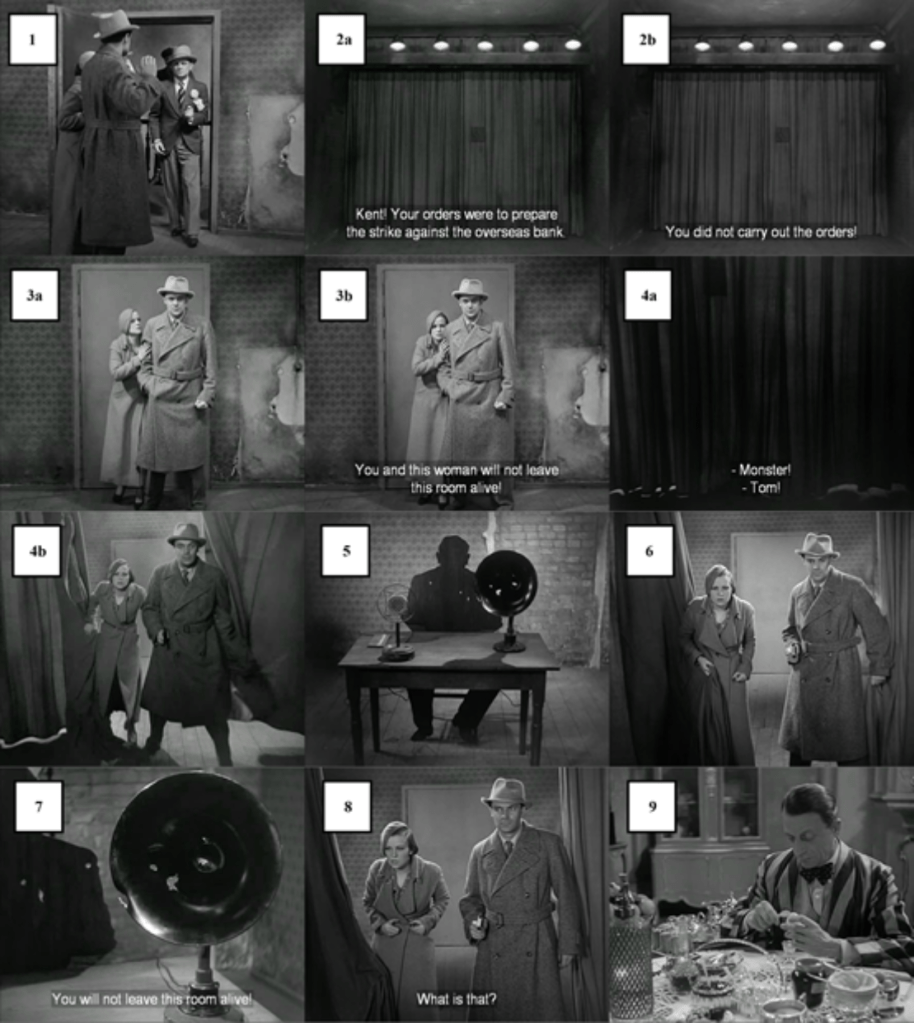

In ‘The Testament of Dr Mabuse’ Lang frequently uses visual rhymes to tie links between shots and sequences. One sequence that clearly highlights these visual rhymes is the section of the film where Kent, a member of Mabuse’s gang who’s refusal to kill has led to him facing a death sentence, and Lilli, an office worker whom Kent has fallen in love with, discover the truth about ‘the man behind the curtain’, the unknown leader of the gang. The sequence begins with Kent and Lilli being kidnapped and taken into the room with the curtain, in which the gang members receive their orders, once they are in the room they are told by their anonymous leader that Kent’s refusal to follow orders shall be punished by death, Kent responds by firing several shots at the curtain. The couple then pull back the curtain, expecting to find the dead criminal mastermind, however, they instead discover that the voice of ‘the man behind the curtain’ was coming from a speaker all along, and that the silhouetted figure projected onto the curtain came not from their leader but instead from a cardboard cutout. The couple are shocked by this revelation, but even more shocked to hear from the speaker that they now have three hours to live, followed by the ticking of a bomb. This climactic moment of the film then cuts to a shot of another member of the gang having some breakfast (shots 1 through to 9). The juxtaposition between the tension, revelation and drama of Kent and Lilli’s predicament and the mundane, everydayness of the gang member eating is expertly fused via Lang’s use of rhymes; the ticking down of the bomb fading into, and being replaced by, the tapping of a spoon on an egg. In this bridge between two different scenes, Lang both covers up the gap and draws attention to it, Tom Gunning, in his study of Lang’s work, notes how ‘the ticking of the bomb mixes into the rhythmic tapping of a spoon against the shell of a soft boiled egg as Lang cuts to one of the gangsters eating breakfast. Where does the ticking sound come from? Anywhere I choose, responds Lang’ (Page 154. Gunning, Tom. 2000), Lang uses this visual rhyme not only to connect the two events but to mock the desperation of Kent and Lilli.

As this transition shows, Lang’s filmmaking often includes an element of wit and self-awareness, not only at the expense of the films characters, but also by playing with the audiences expectations. During this sequence, Lang uses audiences preconceived knowledge of the room to add to the tension and suspense. Kent shooting at the curtain (shot 3) is presented in a shot of Kent and Lilli where the curtain is positioned behind the camera, the typical way in which the room has been shown throughout the film. ‘The following shot,’ (shot 4) Gunning explains, ‘reflects the perverse playfulness of this whole film ….

“We see the curtain and hear the gun shot, the curtain flutters with movement, hands engage and pull it apart, and we see – Kent and Lilli. After the gunfire we expected a shot of the curtain, a reverse angle shot from Kent and Lilli’s point of view … We do see the curtain, but only after the lovers enter do we realize that this is not a reverse angle” (Page 152-153. Gunning, Tom. 2000)

Lang’s consistent pattern of shooting this clearly established space means that when Lang eventually breaks this pattern, shooting, for the first time, from behind the curtain, the audience are just as caught up in the action as the characters. This ordering of shots adds a delayed reveal to the audience, increasing the tension and drama of the scene, before we see what lies beyond the curtain we see Kent and Lilli’s shocked reaction to it. Lang witholds the reverse shot for as long as possible, using off-screen space to increase the audiences engagement with the film. This pattern that has been established when shooting this space and the subsequent breaking of this pattern at this moment of reveal shows how an example of how Lang carefully and precisly used fragmentation and the sequencing of shots to weave not only the narrative of the film but also the form and structure and the effects that this has on the audience.

Despite ‘The Dark Knight‘ largely being both a critical and commercial success, Nolan did receive some critique for his handling of action, many claiming that Nolan had rendered the action incomprehensible and impossible to follow. Many claim this is reflective of trends in Hollywood at the time, Bordwell noting other features making up these changes including ‘the faster cutting rate, the bipolar extremes of lens lenghts and the reliance on tight singles’ (Page 20. Bordwell, David. 2002). In defence of his own work receiving similar crticism, director Michael Bay argued that ‘most people simply consume a movie and they are not even aware of these errors’ (Page 55. Shaviro, Steven. 2016).

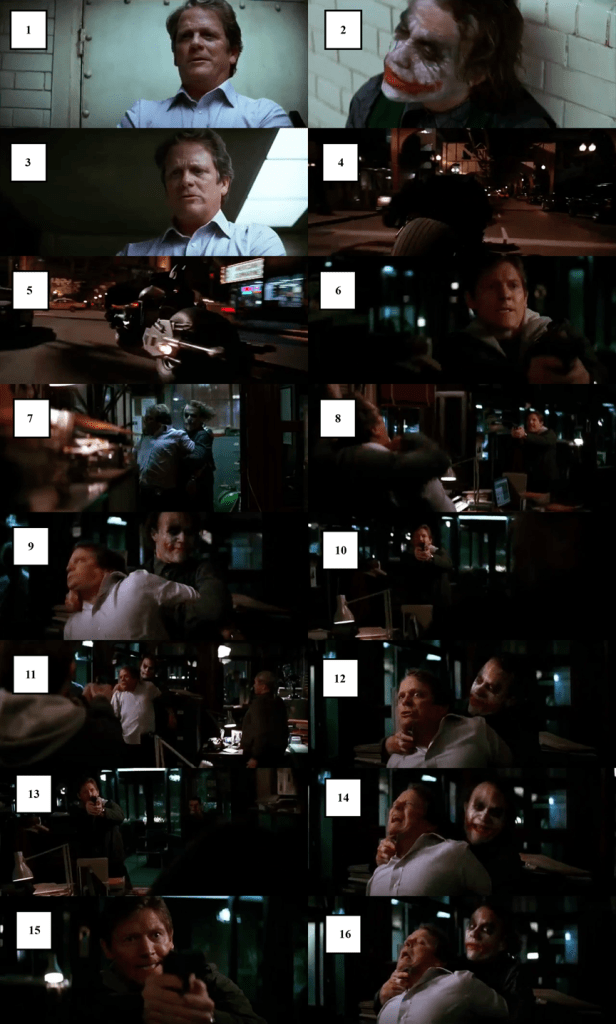

One sequence in particular which highlights how Nolan’s work in ‘The Dark Knight‘ matches up with these trends is the sequence in which we see how the Joker escapes from police custody. While the Joker executes his escape plan we are simulaneously being shown Batman and Lt. James Gordon speeding across Gotham, Harvey Dent and Rachel confessing their love to each other via radio while tied up and facing impending death, and the Joker’s henchman who is rigged to blow up being searched by the police. The ordering of the narrative strands which make up this section seem to be fragmented with little regard for continuity or rhythm, reshuffling the fragments into a different order would have little effect on the scene. However, the Joker’s escape from police custody is the most difficult thread to follow. The Jokers escape begins with him taunting the guard tasked with keeping him in his cell into approaching him, we then cut to a brief 5 second moment of Batman speeding through Gotham traffic, followed by a shot of a character the film hasn’t introduced us to in an office space we aren’t familiar with, reacting to something off-screen. It is soon revealed that this off-screen action the character is reacting to is the Joker holding his guard hostage with a blade to his throat, making his way into the office space and demanding his phone call (shots 1 to 13).

The ordering of events in the sequence shows a lack of continuity and a break in the timeline that the events occupy. The brief 5 seconds we spend with Batman between the Joker in his cell and the Joker holding his guard at knife-point clearly do not represent 5 seconds in the timeline of the Joker’s escape. This brief moment leaves the sequence feeling confused and like something is missing, the action of the scene is the Jokers escape, but the crucial element of his escape, him overpowering the guard, isn’t shown to us. However, even without this moment, introducing the escaped Joker through a shot of an unknown character reacting to an unknown off-screen action underplays the importance of this moment, if the action was reordered and we instead followed the Joker into this space and then saw the reacting police officer the sequence would run more smoothly, operating with concrete off-screen space as opposed to imaginary off-screen space. The shots used in the interaction between the Joker and the nameless character also make the sequence messy and hard to follow. Throughout the sequence the positioning of the camera in relation to the Joker and the policeman change with almost every shot, this means that the direction the policeman’s gun is pointing is different in every shot, in shot 6 he is aiming to his right, in shot 8 he is pointing to his left, and in shot 10 the Joker appears to be directly in front of him. This contant movement makes this sequence unneccasarily confusing, sticking with a more fixed, classical Hollywood shot/reverse shot set up would better establish the space and make the action more understandable. For many the issues raised in the conversation about continuity and the move away from it are not of importance; pointing out issues of continuity has been described as ‘nitpicking’, however, it is in moments like this when the move away from continuity clearly has a greater impact, in the films of chaos cinema ‘narrative is not abandoned, but it is articulated in a space and time that are no longer classical. For space and time themselves have become relativized or unhinged’ (Page 57. Shaviro, Steven. 2016).

From these two sequences the different approaches both directors took towards découpage and the fragmentation of events can be seen, and each director appears to be largely working with the trends of their respective times. Lang was an early adopter of the still somewhat new continuity cinema, his work in visual rhymes, which can be clearly seen throughout ‘The Testament of Dr Mabuse’, was groundbreaking and something which was quickly taken up by others. While Nolan was working in a similarly new era of filmmaking, the era of post-continuity, where filmmakers were treating action in a more avant-garde and expressive way rather than worrying about keeping it clear and easily followable.

Bibliography

D. Bordwell (2002) ‘Intensified Continuity: Visual Style in Contemporary American Film’ pg. 16-28 in ‘Film Quaterly, Volume 55’, University of California Press Journals, California.

In The Cut Part 1: Shots in the Dark (Knight) (Jim Emerson, 2011)

S. Shaviro (2016) ‘Post Continuity: An Introduction’ pg. 51-64 in (eds.) S. Denson , J. Leyda ‘Post-Cinema: Theorising 21st Century Film’, Reframe Books, Falmer.

T. Gunning (2000) ‘Pay No Attention to that Man behind the Curtain’ pg. 146-155 in T. Gunning ‘The Films of Fritz Lang: Allergories of Vision and Modernity’, British Film Institute, London.

The Dark Knight (Christopher Nolan, 2008)

The Testament of Dr Mabuse (Fritz Lang, 1933)